01 Aug The Need for Meaningful Oversight

Aaron Halegua, Jennifer Rosenbaum and Mariam Bhacker

Original Post at Marianas Variety

*Any views expressed in this article are those of the author.

WE are individuals and groups concerned by the labor abuses that transpired at the Imperial Pacific construction site.

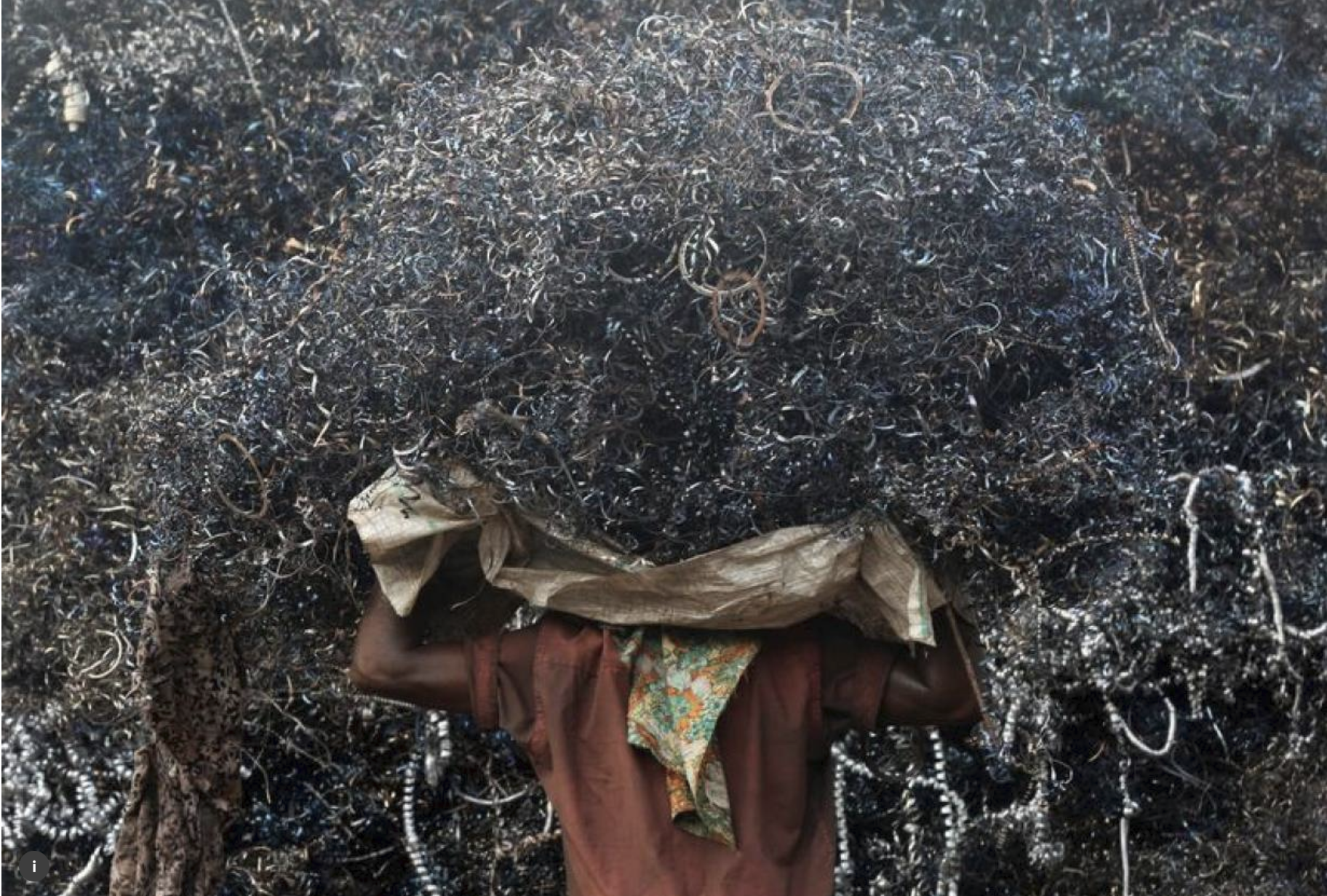

The confiscation of worker passports, failure to pay workers the minimum wage, high rates of injury and even deaths, and retaliation against complaining workers have all been well-documented. In order to prevent future exploitation, we support the proposal to establish an independent and transparent monitoring mechanism in which the voice of workers and their representatives plays a crucial role.

Imperial Pacific promises that the situation has been remedied because it terminated the previous contractors. In fact, a significant risk remains. As the Financial Times recently noted, the construction industry as a whole is a “particularly high-risk sector for worker exploitation.” Further, Imperial Pacific’s workforce now primarily consists of foreign H-2B workers. Not surprisingly, this program that allows companies to bring in cheaper, short-term workers is rife with abuse. From 2010 and 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor identified nearly 1,000 employers that violated H-2 laws. Moreover, statistics reveal that immigrant construction workers are more likely to get injured.

In other contexts where serious worker abuse was discovered, an independent monitoring mechanism was established to ensure compliance with labor and safety rules. An example of this is the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, negotiated after the Rana Plaza factory collapsed killing over 1,100 workers, in which clothing retailers agreed to establish an independent monitoring regime overseen by a steering committee comprised of brands, global unions, and neutral experts. In Qatar, upon reports of widespread abuse of foreign workers building sites for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, the local organizing committee established a monitoring framework to ensure contractors’ compliance with a set of worker protection standards. As part of the auditing regime, an independent monitor was hired to assess companies’ compliance with the standards and an agreement was concluded with the global union, Building and Wood Workers’ International, to jointly conduct health and safety inspections. In both examples, a central tenant of promoting transparency and accountability is that reports by the monitoring bodies are made public.

The logic underlying these programs is simple: we cannot rely on companies to police themselves and the actors at the top of the supply chain or construction project must use their leverage to ensure compliance by subcontractors. Further, government enforcement agencies have limited resources to detect violations, let alone prevent them.

If Imperial Pacific is serious about eradicating abuse from its projects, it too should conclude a binding agreement requiring that its contractors adhere to specific local, national and international standards on labor, safety, and human rights. An independent party should conduct regular audits and publish the results. Any violations should trigger defined, mandatory penalties. Worker organizations should also be permitted to educate employees in their native language about worker rights, grievance mechanisms, and protections from retaliation. The specifics should be negotiated with organizations that genuinely represent worker interests, who then play an ongoing role in ensuring its rigorous implementation and impact on workplace standards.

These proposals are not radical steps. They are recognized “best practices” emerging in the construction sector and established in other industries. Imperial Pacific should embrace this opportunity to join firms that are leading their industries in ensuring workers’ rights and safety.

But Imperial Pacific must not be allowed to simply monitor itself — the Commonwealth’s recent experience in construction and long experience with the garment sector show this to be true. The CNMI government is aware of the need for meaningful oversight and should take this opportunity to turn the industry around. Government authorities told the U.S. Congress, international media, and other stakeholders that CNMI is committed to protecting workers. It is time to make good on these statements by requiring Imperial Pacific to establish a negotiated, transparent and independent monitoring program as a condition for continuing operations in the CNMI.

Aaron Halegua is research fellow of the New York University School of Law. This opinion is submitted in his personal capacity and not as a representative of New York University.

Jennifer Rosenbaum is with Global Labor Justice while Mariam Bhacker is with Business & Human Rights Resource Centre.