27 Jun History Is Made — ILO Adopts Convention To Stop GBV At Work!

History Is Made — ILO Adopts Convention To Stop GBV At Work!

Jennifer (JJ) Rosenbaum

*Any views expressed in this article are those of the author.

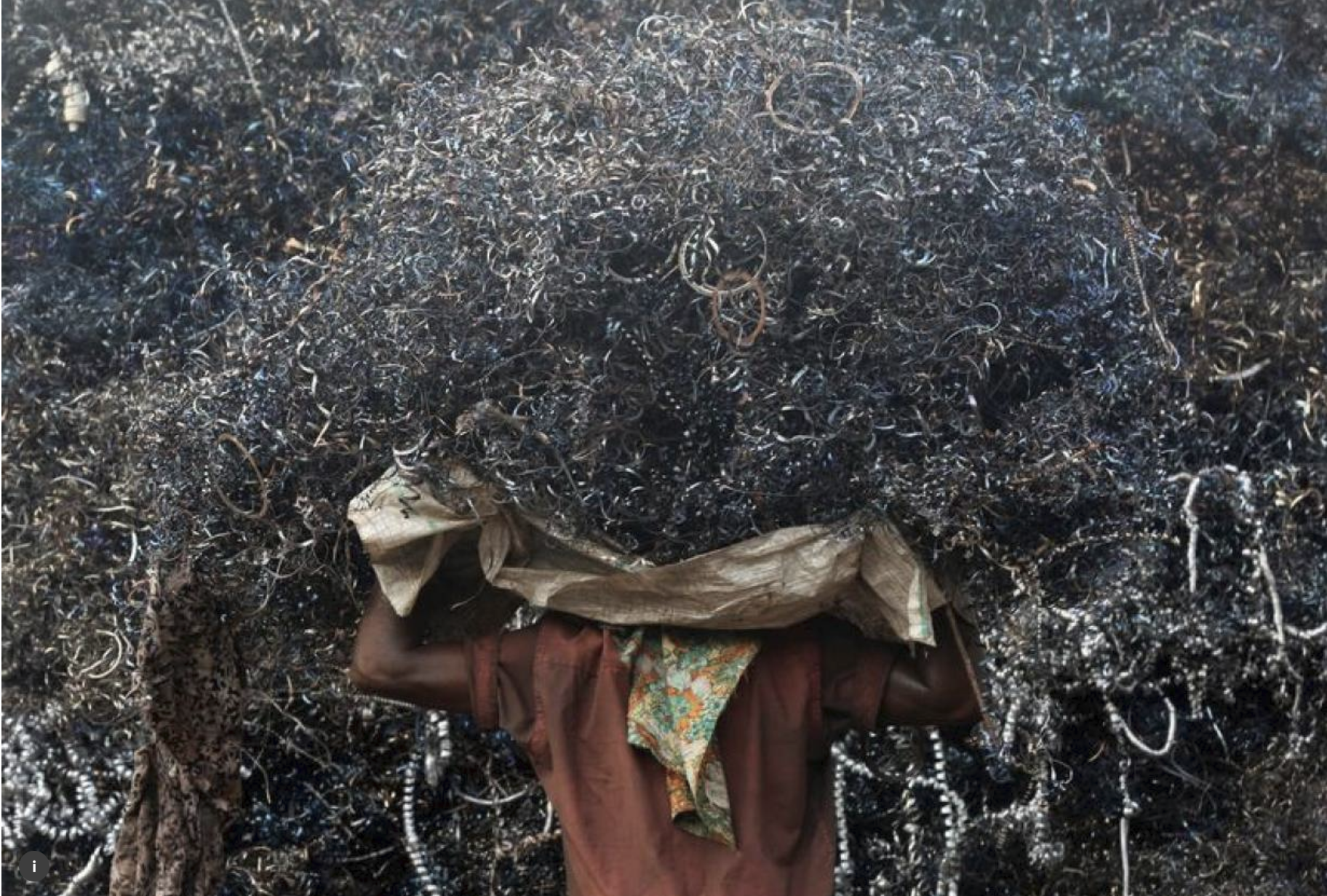

Last week, in a historic close to its Centenary Conference, the International Labor Organization in Geneva voted to adopt a global convention and recommendation on eliminating gender based violence at work. Global Labor Justice (GLJ) and the Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) supported the inclusion of protections for global supply chains and the elevation of human rights principles. GLJ also supported women trade union leaders to participate in these negotiations and plan together for the next phase of ratification and implementation.

These international labor standards provide a framework; but they are only a first step. Eliminating gender based violence in garment supply chains and across all sectors will require workplace programs involving brands, suppliers, and unions with strong women’s leadership.

GLJ’s new report titled, “Gender Justice on Garment Global Supply Chains: An Agenda to Transform Fast-Fashion”, provides a clear road map for fast fashion brands on how to end gender based violence and harassment (GBVH) on garment production lines, along with a set of recommendations to the ILO.

The report uplifts the AFWA’s Safe Circle Approach — a transformative approach to GBVH prevention that integrates key components of a corporate accountability approach. AFWA’s safe circle approach was designed by the AFWA Women’s Leadership Committee in partnership with women workers on production lines and their trade unions, supplier factories and brands. It was created in response to GBVH in garment factories to develop and sustain a positive organizational culture on garment production lines.

You can read the report here.

Going forward GLJ will use the #GarmentMeToo campaign to support the call from the

Asia Floor Wage Alliance’s Women’s Leadership Committee for a commitment from multinational brands employing tens of thousands of women in the global south to implement the Safe Circle strategies approach.

This is a historic moment for gender justice — and it is only the beginning. Transforming workplaces and global supply chains to meet the challenges posed by global inequality and the gender gap requires a gender lens. More important, the leadership of women in trade unions and civil society organizations is a must to face these challenges along with rising fascism, xenophobic nationalism, and climate change.

We hope you will continue to stand with Global Labor Justice and its partners to defend freedom of association and elevate women’s leadership in organizing and bargaining.

Please help us mark this moment. Here you’ll find some sample social media posts that you can use to promote the release of today’s reports, and you can keep up with the latest from us by following us onFacebook andTwitter. Follow additional updates from GLJ and our partners on our blog.

Onward towards eliminating gender based violence in garment production network and expansion of freedom of association and collective bargaining that enable women workers to be change agents in the global economy!

In solidarity,

Jennifer (JJ) Rosenbaum

U.S. Director, Global Labor Justice

Looking Forward with Global Labor Justice:

Labor Migration

In the coming months, GLJ will be releasing new research as part of its Labor Migration Program. Perspectives on Migration Governance is a series of research papers aimed at informing critical debates on migration governance with a bold vision around a future of work in global labor markets that promotes gender equity, labor rights, and democracy for migrant workers.

Global Value Chains

GLJ continues its program to hold international financial institutions accountable to decent work including global labor peace agreements at the finance level. More information on this work is available here.

Global Supply Chains and Gender Justice

Ending gender based violence and harassment (GBHV) is one key component of bringing a gender justice approach to global supply chains- specifically fast fashion.

GLJ’s report —Gender Justice on Garment Global Supply Chains: An Agenda to Transform Fast-Fashion—is the first in a series that will provide a roadmap for international legal frameworks, criteria for corporate accountability initiatives, and a transformative new prevention approach from the Asia Floor Wage Alliance to end GBVH on garment production lines.

The Global Labor Justice series, Gender Justice on Garment Global Supply Chains: An Agenda to Transform Fast- Fashion, lays out six pillars of a gender justice approach:

- Pillar 1, End Gender Based Violence and Harassment: Gender Justice on Garment Global Supply Chains, An Agenda to Transform Fast-Fashion

- Pillar 2, Advance Economic Security: Protect Workers as Supply Chains Relocate

- Pillar 3, Incorporate a Gender Lens into Living Wage Frameworks

- Pillar 4, Uplift Women’s Leadership in Organizations and Advocacy

- Pillar 5, Promote Decent Work and Fair Migration in the Garment Sector

- Pillar 6, Shift Coercive Supply Chain Practices that Contribute to and Constitute Forced Labor

The series will analyze key barriers to gender justice and proposes a bold and transformative vision of work with dignity and economic security for women workers led by women worker leaders involved in national and regional worker organizations. Each Pillar sets out concrete solutions to advance gender justice on garment supply chains, including recommendations for new international labor standards and interpretations, and innovative roles for supplier unions, allied unions, women’s organizations, human rights organizations, and consumers in production and retail countries.

Through this series, women worker leaders on Asian garment supply chains draw from their deep experience to show us the way forward.