Jennifer Rosenbaum & Shikha Silliman Bhattacharjee, openDemocracy

Original Post at Truth Out

*Any views expressed in this article are those of the authors.

In the last week of May and first week of June 2018, trade unions, governments, and employers convened at the International Labor Organization’s 107th Session of the International Labour Conference in Geneva to negotiate an international standard on gender-based violence. The ILO Tripartite Committee ultimately decided to move forward towards trying to adopt a convention and recommendation at the close of negotiations in 2019. However, the position of employers at the negotiating table remained ambivalent and the voice of multinational brands was missing.

Despite research by the ILO and others showing patterns of gender-based violence across global value chains and sectors including garment, hospitality, domestic work, and others, only a handful of corporate voiceshave spoken out in support of a convention – most recently from Gap and H&M. Indeed, the move toward a convention was adopted over the objection of employers.

Newly released research by the Asia Floor Wage Alliance, Global Labor Justice, and partners shows the importance of brands and employers joining with unions and governments to support a strong convention. Research findings call for brands to recognize violence and harassment and take steps to end these violations through an approach that brings worker organizations to the table.

The Spectrum of Gender-Based Violence at Work

In her piece, “From #metoo to a global convention on sexual harassment at work”, Cathy Feingold, the global director for the AFL-CIO, laid out the important initiative trade unions have taken to bring gender-based violence to the top of the ILO’s agenda. Additionally, their work has negotiated a strong convention that provides a framework for trade unions, employers, and governments to each play a role in eliminating gender-based violence in the workplace, broadly defined, and to strengthen freedom of association and worker organizations in critical ways.

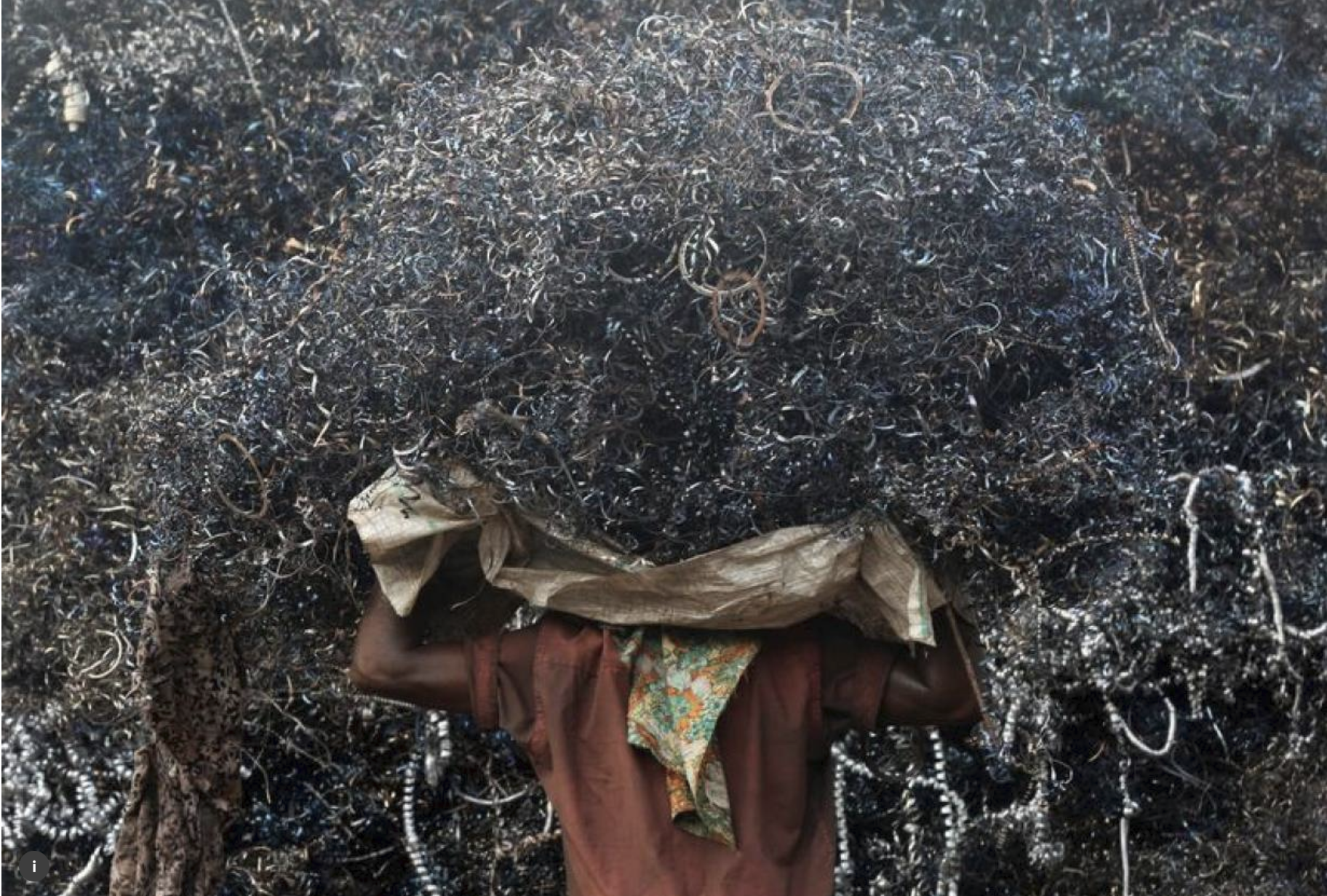

On 25 May 2018, our global coalition of trade unions, worker rights and human rights organizations, released new, factory level research detailing gender-based violence in Gap, H&M, and Walmart’s Asian garment supply chains. This report provides an empirical account of the spectrum of gender-based violence and risk factors for violence that women workers face in garment supply chains. This includes findings from a new investigation of gender-based violence in Gap, H&M, andWalmart’s garment supply chains, conducted between January 2018 and May 2018 in Dhaka, Bangladesh; Phnom Penh, Cambodia; West Java and North Jakarta, Indonesia; Bangalore, Gurgaon, and Tiruppur, India; and in Gapaha District and Vavuniya District, Sri Lanka.

The data was collected through focus group discussions with 150 women workers from 37 different factories supplying garments to Gap, H&M, and Walmart, and found that women workers are routinely subjected to a broad spectrum of violence. Our research found that women garment workers may be targets of violence on the basis of their gender, or because they are perceived as less likely or able to resist.

In particular, one respondent’s experiences offer specific insights into the risk factors that leave women workers in garment supply chains exposed to violence. Radhika, a woman worker employed in an H&M supplier factory in Bangalore, Karnataka, India reported physical abuse associated with pressure to meet production targets. Radhika described being thrown to the floor and beaten, including on her breasts:

On September 27, 2017, at 12:30 pm, my batch supervisor came up behind me as I was working on the sewing machine, yelling “you are not meeting your target production.” He pulled me out of the chair and I fell on the floor. He hit me, including on my breasts. He pulled me up and then pushed me to the floor again. He kicked me.

Radhika filed a written complaint with the human resources department at the factory. She described the meeting between herself, the supervisor, and human resources personnel:

They called the supervisor to the office and said, “last month you did the same thing to another lady – haven’t you learned?” Then they told him to apologize to me. After that, they warned me not to mention this further. The supervisor and I left the meeting. I went back to work.

Radhika reported that the harassment from her manager did not stop, but that she continued to work at the factory because she needs the job: “My husband passed away and I have a physically challenged daughter who cannot work. That is why I need the job. I suffer a lot to earn my livelihood.”

In the H&M supplier factory where Radhika worked, women are concentrated in operator roles, as line tailors and helpers in the production department – a microcosm of gendered hiring practices in garment global production networks. Across Asia, women garment workers make up the vast majority of garment workers. In Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka, women workers represent between 80-95% of the garment workforce. In India, women account for between 60-75% of the garment workforce. Women rarely, however, hold management and supervisory positions.

The experiences of gender-based violence in garment supplier factories documented in these reports are not isolated incidents. Rather, they reflect a convergence of risk factors for gender–based violence in Asian garment supply chains that leave women garment workers systematically exposed to violence.

Our research found that risk factors for violence in garment supply chains are a by-product of how brands like Gap, H&M, and Walmart do business. The structure of production in global production networks (GPNs), involving several companies across multiple countries, allows brands and retailers to dictate sourcing and production patterns while deflecting accountability for how purchasing practices drive violence, harassment, and severe violations of rights at work.

Concentration of Women Workers in Subordinate Roles

Women are disproportionately impacted by patterns of violence in garment supply chains because they make up the vast majority of garment workers in Bangladesh (80%), Cambodia (90-95%), India (60-75%), Indonesia (80%), and Sri Lanka (85%).

Despite their numerical majority within the garment sector, women workers remain within low skill level employment and rarely reach leadership positions in their factories and unions. Detailed factory profiles reveal that at the factory level, women workers are concentrated in the production department, in subordinate roles as machine operators, checkers, and helpers in production departments.

Researchers also completed in-depth factory profiles of 13 garment supplier factories, including five factories from Bangladesh, five factories from Cambodia, and three factories from India. These factory profiles provide a demographic snapshot of the garment supply chain workforce that demonstrates the concentration of women workers in temporary, low-wage production jobs within the garment supply chain. Factory profiles also sought to understand working conditions, presence of trade unions and dispute resolution mechanisms.

Risk Factors for Gender-Based Violence in Supply Chains

The experiences of gender-based violence documented in our new reports on gender-based violence in Gap, H&M, and Walmart garment supply chains are not isolated incidents. Rather, they reflect a convergence of risk factors for gender-based violence in supplier factories that leave women garment workers systematically exposed to violence.

Our research sought to document working conditions that place women garment workers at routine risk of gender-based violence. For instance, researchers documented extreme pressure to complete production targets where women face routine physical violence including slapping and throwing large bundles of clothes and smaller sharp projectiles, such as scissors; and verbal abuse. Researchers also documented barriers to reporting workplace violence, including high levels of job insecurity and threats of firing among temporary workers. Finally, by completing detailed ‘day in the life’ accounts, researchers documented deprivations of liberty including being forced to work through legally mandated breaks, forced overtime, and relocation of workers between factories and buildings without prior consent.

Risk factors in garment supply chains are a by-product of how multinational corporations do business. These risk factors stem from the structure of garment supply chains, including:

- asymmetrical relationships of power between brands and suppliers in garment supply chains;

- brand purchasing practices driven by fast fashion trends and pressure to reduce costs; and

- proliferation of contract labor and subcontracting practices among supplier firms.

These routine industry practices have a profound impact on Bangladeshi, Cambodian, Indian, Indonesian and Sri Lankan women workers. By analyzing cases of violence reported by women garment workers, we identified a series of risk factors for violence and barriers to accountability.

Risk Factors for Violence:

- Short term contracts

- Production targets

- Failure to pay a living wage

- Excessive hours of work

- Unsafe workplaces

Barriers to Accountability:

- Unauthorized subcontracting

- Denial of freedom of association

- Lack of independent monitoring

Drawing upon our 2016 research on violations of fundamental rights at work – including structured interviews with 745 workers employed in 105 factories in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India – our reports demonstrate that these risk factors and barriers to accountability are widespread in the Gap, H&M, and Walmart garment supply chains.

Multinational Brands Must Speak Out

The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Standard Setting Committee is now halfway through its important work. In June 2019, negotiations will begin again coinciding with the hundredth anniversary of the ILO with the goal of finalizing a convention and recommendation.

Action from US-based multinational brands is important. Walmart and other brands should join H&M and Gap in publicly supporting and committing to proactively implement an ILO convention and recommendation on gender-based violence that includes the recommendations from the Asia Floor Wage Alliance and partners.

H&M, Gap, and Walmart should also meet with the Asia Floor Wage Women’s Leadership Committee in the next three months to discuss the supply chain findings and next steps, including proactively working with the Asia Floor Wage Alliance to pilot women’s committees in factories that aim to eliminate gender-based violence and discrimination from supplier factories.

So far there has been no direct response. Gap and H&M have said they will engage in internal audits with their suppliers. Disappointingly they have not reached out to the trade unions. It is not enough to have so-called corporate social responsibility policies, which new research further shows are insufficient to alone deliver decent working conditions to women workers.

Women workers and their labor organizations are uniting across borders to demand work that is free of gender-based violence, pays a living wage, and promotes women’s initiative and leadership at all levels. Multinational corporations are expanding global supply chain models in many sectors. But it’s not only the corporations that are going global. Intersectional movements of workers, women, migrants and others are building cross-border networks and demanding change to a system that relies on poverty wages and gender-based violence to deliver fast fashion to the US and Europe at the expense of the well-being of women garment workers and their families.